An Understanding of Italy's Economic Failure: The EU's Weak Underbelly

A Rejection of the Mainstream Economic BS

This is a summary on an excellent paper written by Dario Guarascio, Phillip Heimberger, and Francesco Zezza entitled “The Eurozone’s Achilles Heel: Reassessing Italy’s Long Decline in the Context of European Integration and Globalization” in the Italian Economic Journal May 2023.

In the post-WW2 era, the Italian economy was much more dominated by small firms characterized by low productivity than other European nations. Micro-enterprises provided over a quarter of economic value added, versus only 13% in Germany, 17% in France and 22.4% in Spain. Such small and micro enterprises tend to lead to a lack of research and development spending. In Italy, this was exacerbated by lower levels of state spending on education. The state owned IRI acted as a holding company for larger enterprises, and especially in the 1960s invested heavily in capital intensive sectors. It was involved in such areas as “steelmaking, mechanical-shipbuilding and telecommunications as well as in the construction of national motorways and other large infrastructural projects”. The smaller enterprises benefitted from these investments as well as the transfer of new production techniques and learnings from these larger enterprises. In effect, the state-owned IRI acted to offset the shortcoming of the small and micro enterprise orientation of the Italian economy. IRI also contributed directly to the industrialization of the south of the country that had historically lagged behind the north.

The owners of small firms benefitted from regulations that allowed them to have more flexible labour contracts, access to tax breaks and fewer governance requirements than larger companies. Many were also family businesses where important management positions may have been awarded more due to familial linkages than competence and merit. Such practises would also tend to keep more able employees away as they would see their upward trajectory blocked. Together with their lack of investment and R&D such firms tend to have relatively low productivity and low wages. Italian firms employing over 250 employees show the same productivity as German ones, and firms with 50-249 employees have the highest productivity among their European peers. But these two types of companies are only responsible for 37.2% of employment, versus 61.6% in France, 59.2% in Germany and 44.4% in Spain. Much of the larger enterprises were located in the north, with the south more dominated by smaller enterprises. The Southern Italian Development Fund (SIDF) offset this somewhat by focusing on investments in capital intensive areas in the south. In addition, the extension of the welfare state lead to fiscal transfers from north to south - improving market conditions for many companies in the south.

Strong labour unions had kept wages high, especially in the larger manufacturing companies. Contrary to the teachings of mainstream economists, such wage pressure can be a societal good in driving firms to invest in productivity-enhancements which increase value added per employee and in lifting general living standards. Easy access to cheap labour, through the destruction of unions and the availability of cheap immigrants tends to focus firms away from making investments in such productivity enhancements.

As Italy entered the 1970s, the first and then second oil shocks hit hard on a nation with little or no domestic oil and gas production. But up until the 1980s, Italy was still a relatively successful economy. It was only with the drive for European integration in the 1990s that Italy started to falter, and then suffered decades of stagnation. The rapid deregulation of the capital account, the end of state interventionist policies (both due to neoliberal politicians and limitations upon state intervention within the EU), the dismantling of many state owned enterprises, and welfare state “reforms” that penalized wages and therefore reduced consumer demand, came together to deconstruct the Italian success. The crushing of the unions in the 1970s and 1980s further diminished wages and limited demand in the economy. With membership of the Euro, Italy was also unable to devalue its currency with respect to the much stronger and productive northern economies such as Germany. Instead, internal deflation was the only avenue available which represented the probability of a deflationary trap as weakened demand both weakened government finances and domestic businesses. Italy was left with all the negatives (dominance of small businesses, north-south divide, lack of educational investment) and none of balancing positives.

Within the EU fiscal straight-jacket a long run state investment plan is not possible, and instead a deflationary trap of strict fiscal policies and market liberal reforms has been in place. During the Euro crisis, Italy lost 25% of its industrial production (with losses more predominant in the south) and the EU straight-jacket greatly restricted the state’s ability to aid any recovery. Public expenditures in the south also fell more than in the north, further exacerbating the north-south divide. As the authors put it, Italy’s membership of the EU may have been on-balance negative for the country:

Our results suggest that Italy is a failed case of modernisation brought on by external constraints. Euro area membership did not result in modernisation and convergence towards higher living standards such as those experienced in Europe’s best performing countries. On the contrary, a fault line opened up between the core – centred around Germany’s industrial export hub – and the southern periphery, including Italy.

As the core strengthened its industrial base, accumulating large trade surpluses, Italy (and to a certain extent, other parts of the southern periphery) experienced a process of structural weakening or ‘poor tertiarisation’. Productive and technological capabilities declined while the relative importance of low-tech-low-wage service sectors increased.

Recent governments have attempted to regain competitiveness by putting further pressure on wages through further labour market deregulation, and also large-scale immigration. This simply traps the Italian economy in a low wage spiral, as companies are not incentivized to make productivity enhancing investments at the same time that the state is unable to provide any support for such investments.

Corrected for domestic inflation, Italy’s GDP flat-lined during the 1990s, then grew in the early years of this century to peak in 2008. It has never regained that level, and was still 9.5% below that level in 2023. GDP per capita is where it was in 2007, and hardly above the level of 2001. With an increasing level of income and wealth inequality, real wages in 2023 were 4.4% below their level in 1990!

At the same time, the country had a fiscal deficit of 3.4% of GDP in 2024, a government debt of 135.3% (forecast to be 140% in 2026), and a growth rate of 0.7% (nominal of 1.7% with 1% inflation), and a government 10-year interest rate of 3.615% on April 28th 2025. In 2025, the country is projected to grow perhaps at 0.5% with the US tariffs a possible downside risk. The country had a current account surplus of 1% of GDP in 2024, mainly due to its low growth with respect to other nations; i.e. internal deflation limiting domestic demand. And of course, Italy has no control over monetary policy as that is controlled by the European Central Bank (ECB).

Negative natural population change is now in the region of 300,000 a year (overall population 59 million) as the poor outlook and low wages help reduce the birth rate. Recent net migration levels have offset much of the natural population fall, aided by the influx of 160,000 Ukrainian refugees, but this masks a reality of the Italian educated young tending to leave the country for better prospects and being replaced by less educated immigrants. The vast majority of immigrants reside in the north of the country, exacerbating the north-south divide as the south depopulates due to the increasing rate of natural decrease (births - deaths); hence the increasing number of empty properties and falling property prices in the south.

At the same time, competition from China is ramping up across more and more advanced sectors - evidenced by the increasing presence of Chinese electric vehicles in the Italian market. This has exacerbated the woes of Fiat and the other Italian brands owned by Stellantis (e.g. Alfa Romeo, Abarth and Maserati), with an increasing probability of the end of any relatively high volume car production in Italy. With the obvious impacts across the whole Italian auto supply chain. China is also rapidly becoming dominant in the fields of industrial machinery and robotics, both important Italian sectors dominated by small firms.

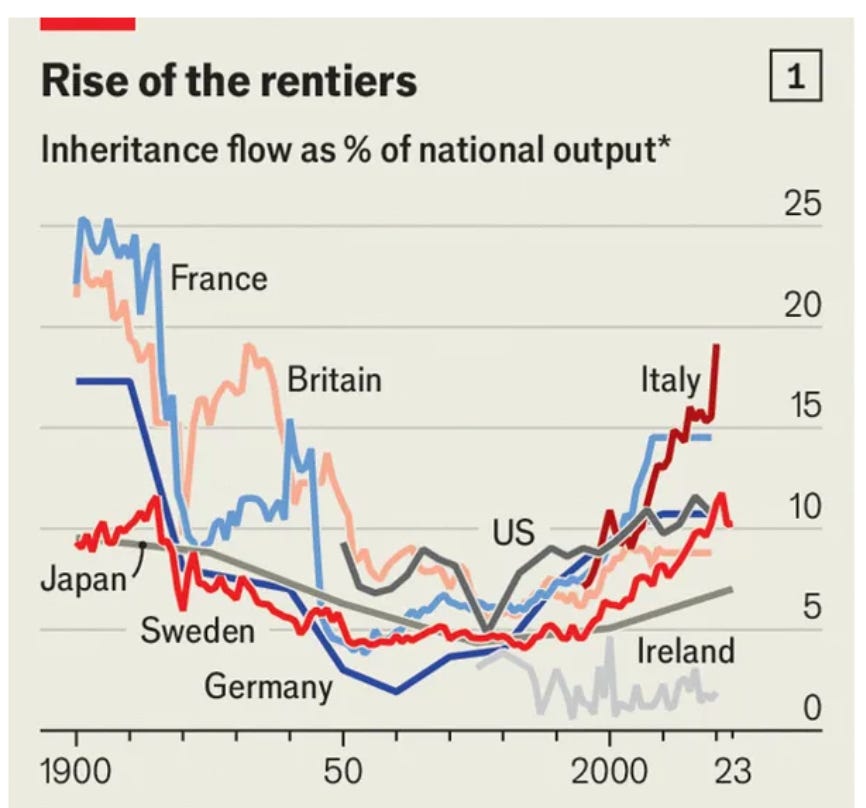

The size of Italy’s economy, 11th biggest in the world and third biggest in the EU by PPP, 8th and 3rd by nominal GDP, is on a very different scale to that of Greece. It is truly the weak underbelly of the EU, on a non-sustainable economic and financial path. In 2024 Italy’s total fertility rate (TFR) continued to fall to 1.18, and at least some of this may be laid at the door of the greatly increased level of precarity of the young as labour “reforms” delivered “flexible” employment contracts that offer little stability or career paths. Together with the related low wages, this has driven Italy’s youth to move abroad where they can enjoy both higher wages and the chance of a real career. Not helped by nepotism and cronyism within family-owned businesses. All the while, the proceeds of inheritance become a greater and greater share of GDP; creating a new class of idle rentiers. Aided by a “staggeringly low” inheritance tax, which is part of a highly regressive tax system.

Economist via @pat_kaczmarczyk

Neoliberalism has also made sure that those that strive for higher education find themselves considerably in debt early in their adult lives. Italy already had a very low level of its population possessing college degrees (lower than Mexico) and is losing many of that small number of new graduates. It is heavily caught in a “brain drain trap” that has become self-feeding. It is striking that Piedmont, perviously the apex of the Italian industrial triangle, is now seeing the out migration of its youth. As the documentary below notes, Italy has lost more than a million of its young adults in the past decade. All facilitated by freedom of movement and employment within the EU (56% of emigrants), and previous migration linkages to the US (39% of emigrants).

Italy may be a wonderful place for tourists, foreign retirees and the Italian oligarchs, but it is an increasingly desolate one for its young educated adults. As the years of youth out migration continue, Italy will increasingly see less mid-career highly productive workers, and businesses will become more and more constrained by the lack of such workers who are the back bone of any company.

Meloni has continued with the neoliberalism and immigration (while publicly attacking the “wrong kind” of immigrants), which merely continues Italy on an unsustainable path. As this article notes:

The unmistakable political shift of attitude in Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and her Fratelli d’Italia party is the latest evidence that European politicians use ideology merely as a vehicle. Once in power, they are governed by the same neoliberal policies that control the rest of Europe.

The next global recession or financial crisis may fully expose Italy’s weaknesses through a financial crisis, with Italy far too big to be bailed out by the EU. The result may an “Italexit” with a return to a Lira that is valued at a much lower level than the Euro. Such a move would be very problematic for Germany, as the advantage it gains from a Euro that is weaker than a German Deutschmark would have been is substantially lost. Further Italian internal deflation is a path to further decline, more government debt, and greater youth emigration. It may be only a matter of time until Italy has to fully face this reality.

In the past few years the Italian economy has outgrown some of its European neighbours, but that is not saying much given the utterly sclerotic nature of those countries. Italy grew at a rate of 0.7% in both 2023 and 2024, vs. a contraction of 0.3% and 0.2% in Germany in those years, a contraction of 1% and 1.1% in Austria, growth of 0.7% and 0.8% in Switzerland, and growth of 1.1% and 1.1% in France. As detailed in the video below, the quicker growth is due to increased government subsidies that were brought in for the COVID pandemic (the National Recovery and Resilience Plan). These subsidies are directed toward home renovations which will not help drive future productivity growth.

These subsidies are also already being cut back due to their unsustainable draw on government spending, and their full withdrawal will remove the boost to GDP growth. The boost in tourism post-COVID will also fade, and the impact of the US tariff war will also be a negative for GDP (Italy had a trade surplus with the US of about 40 billion Euro in 2024). The latest IMF forecast for Italian GDP growth in 2025 is 0.4%, and that may be optimistic. The post-pandemic and Ukraine-war related high rates of immigration (4.8, 4.7 and 4.1 per 1,000 residents for 2022, 2023 and 2024 respectively) may also not be sustainable, and a fall in net immigration will lead to a fall in population as the natural decline rate is not sully offset by new immigrants.

Great article Roger!

If anything, it might be even too optimistic…

A quick anecdote to show how bad the situation in Italy really is: there are LOTS (relatively speaking) of youngish Italian immigrants living in my little corner of Spain. Work opportunities must be very low if the situation in Spain is for them much better than in their home country (in Spain we have a chronic unemployment problem).

Also, the role of the €€€ in Italy’s downfall cannot be overstated. In the 90s / early 00s Germany was in a quite bad situation (i know it bc I was there and saw it firsthand!). But once the full impact of the € and of the ECB’s ultra low rate policies hit, the change was massive. German exports profited from an artificial devaluation while Spanish and Italian industrial goods lost most of their competitiveness. The once excellent industrial equipment and machine tool industry in northern Italy was destroyed. Also, ultra low rates facilitated new investments in German manufacturing and in German firms buying Eastern European rivals, where they set up a low cost supply chain spanning all the way from Ukraine up to Czech Republic, while wage suppression inside Germany shielded the country against the high inflation that spread to the Eurozone periphery. These same low rates fueled the catastrophic real estate bubbles that we saw in Spain, Ireland, etc in 2008.

In short: the € has been the worst thing that has happened to to the Eurozone periphery since the end of WWII…

it seems as though the european union has been a great idea for neoliberalism, but a very bad one for democracy.. now all the countries are beholden to unelected officials whether it be at the european central bank, european commission and etc. etc.. at some point many within europe who are a part of this union will have to call a spade a spade and exit this straight jacket.. but that won't happen before the capitalists get more money out of them, and for leaving too..